CEIC Special Analysis: Effects of India’s Demonetization

By Prithiraj Panigrahi

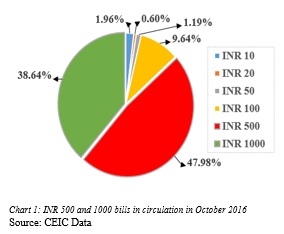

India was stunned November 8 when the government unexpectedly announced the withdrawal of all 500 and 1000 rupee notes from circulation. Most analysts expected that the anti-corruption move would trigger a major economic crisis, but four months later, several leading Indian economists say the worst never materialized and the economy is now beginning to enjoy the benefits of the policy.  Economists had good reason to fear the abrupt move. Normally the 500 and 1000 rupee notes are the workhorses of the Indian marketplace. Generally trading at roughly $7.50 and $15.00 respectively, those two bills represented 86% of all the currency in circulation prior to the announcement. They’re the way India’s small grocers, day labourers, and the rest of the country’s vast informal economy pay and get paid. But the Modi Government decided the notes had to be replaced because they are also believed to play an important role in corrupt transactions. The 500 and 1000 notes are reputedly the stuffing of choice for the briefcases and plastic bags that fuel the black economy, and officials hoped that this surprise attack would hobble the sector’s power.

Economists had good reason to fear the abrupt move. Normally the 500 and 1000 rupee notes are the workhorses of the Indian marketplace. Generally trading at roughly $7.50 and $15.00 respectively, those two bills represented 86% of all the currency in circulation prior to the announcement. They’re the way India’s small grocers, day labourers, and the rest of the country’s vast informal economy pay and get paid. But the Modi Government decided the notes had to be replaced because they are also believed to play an important role in corrupt transactions. The 500 and 1000 notes are reputedly the stuffing of choice for the briefcases and plastic bags that fuel the black economy, and officials hoped that this surprise attack would hobble the sector’s power.

One economist at a major domestic company says many analysts feared a monetary cataclysm. However, he says, they made a mistake. Money always has two functions, he says – it’s a stock of wealth and a medium of exchange – and estimates are floating that some of the 500 and 1000s in circulation turned out to be stashed cash. This was coupled with prioritising currency supply to the towns and rural areas. Thus monetary effects of the withdrawal were more muted than anticipated.

Roadside fruit and vegetable sellers and other small cash-only retailers lost some business, but their loss was offset by a rise in sales to retailers that accept electronic payments. In rural areas, where a monetary shock might have been more likely, he says, the government was quick to get banks, the new bills they needed in time to prevent a large-scale crisis.

Other labour-intensive sectors where people are often paid in cash, such as agriculture, textiles, jewelry, and construction, also took a hit, but a good monsoon season helped keep the economy buoyant, according to Upasna Bhardwaj, Senior Economist of Kotak Mahindra Bank in Mumbai. Looking ahead, however, Bhardwaj expects all those sectors to recover, as the remaining withdrawal limits put in place in November are removed.

In recent years, the number of 500 and 1000 rupee notes in circulation has outpaced the growth of the economy. Between 2011 and 2016, circulation of 500 rupee notes grew 76% while 1000 rupee notes rose by 109%, far outpacing the economy’s 30 percent growth, according to Reuters.

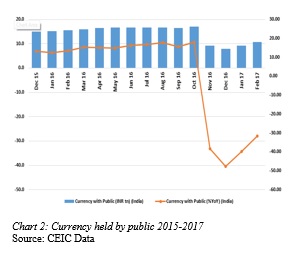

Following the November announcement, the total value of currency in circulation fell dramatically. Currencies of all denominations held by the public dropped in value, from INR 17 trillion in start of Oct 2016 to a low of INR 7.8 trillion in December 2016.

Following the November announcement, the total value of currency in circulation fell dramatically. Currencies of all denominations held by the public dropped in value, from INR 17 trillion in start of Oct 2016 to a low of INR 7.8 trillion in December 2016.

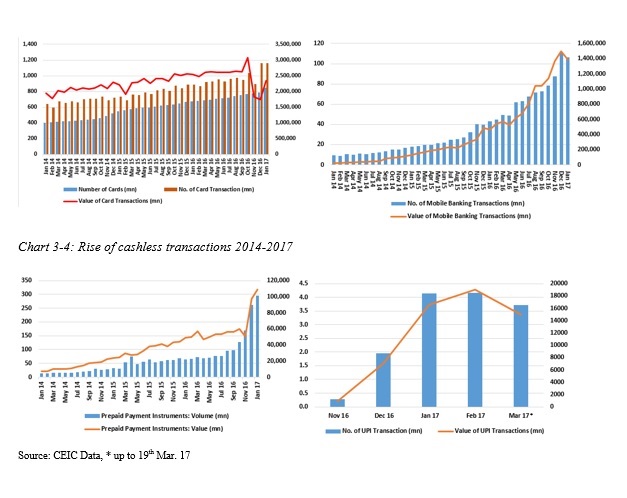

To force people to make more transparent payments, ATM withdrawals were limited to 2000 rupees per day and bank withdrawals to 20,000 per week. These restrictions encouraged consumers to pay more with debit cards and other cashless payment systems, which is quite feasible, given that Indians now carry roughly 1 billion credit and debit cards, up from 545 million just two years ago and 286 million in the beginning of 2012.

The number and value of card transactions jumped in December to 311 million and a value of 522 INR billion from 205.5 billion and a value of 352.4 billion. At the same time, the number of mobile banking transactions also jumped, from 78 million in November to over 110 in December, and then dipped slightly to 106 million in January. Now, however, volumes seem to be subsiding as the new bills have reached the marketplace, to 763 million transactions from 671.5 million in October, and value has even dipped, to 92,594 INR billion from 94,004 INR in October, according to NPCI data. This coincided with a rise in replacement bills in circulation. By February, circulation of the replacement 500 and 2000 notes had grown to 11.07 trillion INR up from 10.64 trillion.

Anecdotally, however, analysts observed that more mom and pop stores and customers are now doing more business with cards. The major company economist counted himself among the converts. “My cash spending literally has been zero over the past two months,” he says. “So whatever little I was spending in cash earlier I am now doing through digital wallets and am doing through my credit card or my debit card.” Nor have his spending habits changed, as his local small grocer has switched to digital forms of payment. Many now use various cellular payment apps.

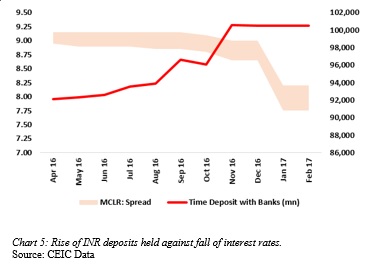

The program has had an impact already on bank deposits. Most of the money that used to squirreled under mattresses has now been deposited, which means it is now out working in the economy. “There was a lot of idle cash also lying in the households and the business houses. And all of that is part of the financial savings now, it’s all in the banking system,” explains Bhardwaj.

The program has had an impact already on bank deposits. Most of the money that used to squirreled under mattresses has now been deposited, which means it is now out working in the economy. “There was a lot of idle cash also lying in the households and the business houses. And all of that is part of the financial savings now, it’s all in the banking system,” explains Bhardwaj.

The major company economist noted that the growth in deposits has been strong enough that banks have been able to reduce their lending rates by 100 basis points. If this structural change holds, even more benefit can be expected. “From here on, if the durable deposits remain in the system, you could expect rates to come down further,” he predicts.

So far, demonetisation has not generated the amount of revenue that the government had hoped, economists say, but that may change. January and February monetary data is not yet available and the Income disclosure programme ends in March.

A second stage of the program that is now beginning, a closer monitoring of suspected tax scofflaws uncovered in the course of the deposit program, will also broaden the tax base, Bhardwaj predicts.

“On the government side, obviously higher tax collection is very much a possibility now,” agrees Suvodeep Rakshit, Economist of Kotak Institutional Equities, in Mumbai, “...because the government has the numbers now in terms of the data, who has a bank account, etc., which obviously the government will use to create more compliance.”

People who deposited a lot of money during the cleanup campaign should anticipate a knock at the door to find out where the money came from, the major company economist says.

Long term, Rakshit sees this as an economic positive too. Today, many individuals and businesses simply don’t pay taxes, he says. The country collects less tax as a percentage of GDP than many countries at its level of development. As compliance improves, the government will have more resources to invest in infrastructure and other improvements that will make the country more productive. CEIC analysts estimate that the Indian tax rate amounts to 11.17% of GDP, in contrast to as much as 30% for developed countries.

The program is also encouraging more people to join the formal economy. “You do not have an incentive for holding that much cash anymore, because you do not know if the medium of exchange will remain the same for a foreseeable period of time,” one economist says.

Bringing more people into the formal economy will improve the tax base, making more money available for infrastructure construction, education, and other country-building initiatives, according to economists.

However, risks remain.

The continued success of the initiative depends on whether the government is able to maintain its present commitment. The recent victory of the BJP in the elections of largely agricultural Uttar Pradesh and 3 other states out of 5 which went to polls in 2017, suggests that the Modi government retains its mandate for reform, but analysts warn enthusiasm could wane.

One important factor is the reliability of the new system. Data security and rural mobile Internet penetration are two crucial concerns that will need to be addressed, the major company economist says.

With demonetisation now passed, some are beginning to look ahead for the next possible shock. Bhardwaj’s nominee: implementation of the new Goods and Services Tax. “With demonetisation coming to an end, the next big thing that people are focusing on is the implementation of GST,” she says.